PSA: Causation without Correlation

Correlation, Causation, and Useless Platitudes

Any student who has taken Statistics 101 can tell you (and will tell you) that “Correlation does not imply causation.” This student is correct - correlation does not imply causation. You need only look at the wonderful Spurious Correlations to see the truth of such a statement. Unfortunately, this platitude is incorrectly interpretted as “a correlation means that there is no causation” far too often. Relevant XKCD:

“Correlation doesn’t imply causation, but it does waggle its eyebrows suggestively and gesture furtively while mouthing ‘look over there’.”

Correlation can Imply Causation

There are situations where merely observing correlation between two quantities does in fact mean that those two quantities are causally linked. There is an entire field of Statistics dedicated to this distinction. The most common method for detecting causation from correlation is in randomized studies. In a properly conducted, well-powered randomized trial, we can guarantee (with some set degree of confidence) that correlations observed are causal in nature. Of course, as with all findings in Statistics, we can never be certain of the causal nature, but with enough well-collected data, we can be as certain as we need to be.

Even without randomization, we are able to detect causal relations from observed correlations. These so-called observational studies tend to be more difficult to use for this purpose (e.g. they require stronger assumptions, more data, a sound theoretical backing, or all of the above), they are still frequently and reliably used for this purpose. Consider the case of smoking and lung cancer. It would be entirely unethical to randomly assign groups of individuals (at birth) to be either smokers or non-smokers, and then follow them and collect information regarding the rates of lung-cancer. Instead, we rely on observational data to detect this causal relationship. We have seen enough times (in enough settings) to know that this is a causal relationship. There is a strong scientific backing explaining this phenomenon, and it has reliably held-up over time.

So while correlation does not imply causation, it can imply causation, given we take into account enough relevant factors. A Statistics 102 student recognizes this fact, and will often then tell you “correlation does not imply causation, but causation does imply correlation”. Unfortunately, unlike the Statistics 101 student from before, this student is actually simply incorrect. Causation does not imply correlation!

Causation does NOT Imply Correlation

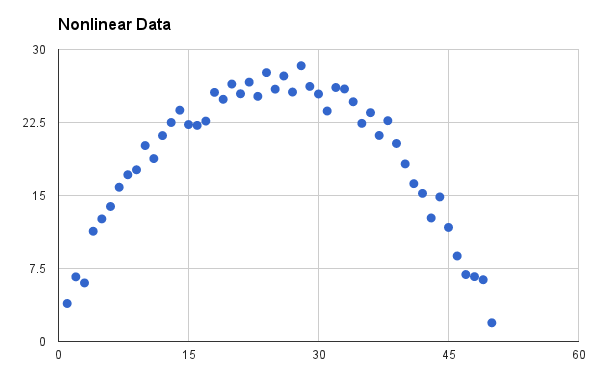

This is counter-intuitive (but true). The reason here has to do with the definition of correlation. When people say correlation, they almost certainly mean Pearson’s Correlation, as this is the most commonly used measure of correlation. Pearson’s Correlation is a measure of the linear relationship between two quantities. This is very useful in many settings, but it only takes a moment thought to recognize that non-linear relationships exist. In fact, the following plot would exhibit a correlation of 0.

Now the two quantities pictured have a very clear relationship, it just happens to be non-linear. As such the correlation is 0. Is the relationship between these two quantities causal? Who knows! But the point is that the observation that correlation equals 0 is a point which gives literally no information as to whether or not a causal relationship exists [I mean, technically it does tell you that it is not possible for it to be a strictly, unmediated linear relationship, but that’s so little information as to basically be no information].

A Set of Concrete Examples

To illustrate the above, we are going to use a set of examples with some real math (don’t worry - it’s not too difficult). These will give you an anchoring point to recognize the difficulty in trying to have a succint statement to capture the interplay between correlation and causation.

- Take \(Y\) to be some outcome - we will simply call it “utility” so that it is hard to argue against my proposed models.

- Take \(X\) to be some measurement about a person - we will simply call it “success” because, again, these are my models! We will assume that \(X\) comes before \(Y\) in time, so that it could be a cause of \(Y\).

- Take \(S\) to be a variable representing the sex of an individual, which will take the value of \(1\) to represent females and -1 otherwise.

Correlation Implying Causation

If we propose that \(Y = 2X\) then \(X\) and \(Y\) have a correlation of \(1\). Now, we assume that we have measured everything about these individuals, and this is the only relationship that exists. In this setting, \(X\) also directly causes \(Y\). That is, an individuals utility is exactly equal to twice their success. Since success comes before utility, success can be said to cause utility.

Correlation without Causation

Now, let’s say that we observe the exact same model \(Y = 2X\), where the correlation is still \(1\). Now, we also make the following observations:

- First, males have a utility of \(-50\) and everyone else has a utility of \(50\)

- Second, males have a success of \(-25\) and everyone else has a success of \(25\)

In this setting, the exact causal mechanism may not be as clear. However, given the above two observations it seems reasonable to propose that \(X\) is caused by \(S\), through the model \(X = 25S\). Similary, it seems reasonable to propose the model that \(Y = 50S\). These two models combine to suggest \(Y = 2X\). However, in this setting we have a confounding relationship.

To clearly state what is happening: Sex causes utility, and sex causes success. There is no causal relationship between utility and sucess, however, because of the confounder sex it appears as though there is one.

Causation without Correlation

Finally, we propose the model \(Y = 2AX\). That is, the utility observed is two times the success of a female, and it is negative two times the success of a male - more successful females have higher utility, more successful males have lower utility.

If we assume that there is no relationship between sex and outcome, and we assume that there is an equal probability of being male or female, then we will find that the correlation between utility and success is exactly 0. However, success still causes the utility, it just acts differently on males or females. If you tell me an individuals sex and their success, I can tell you their utility.

Conclusions

So, what can we say? Well, correlation does not imply causation, except sometimes it does. Further, causation does not imply correlation, unless the relationship is strictly linear. It is certainly less catchy, but also far more accurate, than the standard, so I will understand if it doesn’t catch on!